Simon Wren-Lewis

In the debate over inequality and priorities set off by Ezra Klein’s

article, Kathleen Geier

writes (HT

MT) “the policy fixes for economic inequality are fairly clear: in no

particular order, they include a higher minimum wage,

stronger labor unions, a more progressive tax system, a more

generous social welfare state, macroeconomic policies that promote a

full employment economy, and much more powerful government regulations,

particularly in the banking and finance sector.” And part of me thought,

do we really want to go back to the 1970s?

Maybe this is being unfair for two reasons. First, in terms of the

strength of unions, or the progressivity of taxes, the 1970s in the UK

was rather different from the 1970s in the US. Second, perhaps all we

are talking about here is swinging the pendulum back a little way, and

not all the way to where it was before Reagan and Thatcher. Yet perhaps

my reaction explains why inequality is hardly discussed in public by the

mainstream political parties – at least in the UK.

The 1997-2010 Labour government was very active in attempting to reduce poverty (with

some success), but

was “intensely

relaxed about people getting filthy rich as long as they pay their

taxes.” This was not a whim but a strategy. It wanted to distance itself

from what it called ‘Old Labour’, which was associated in particular

with the trade unions. Policies that were explicitly aimed at greater

equality were too close to Old Labour [1], but policies that tackled

poverty commanded more widespread support. Another way of saying the

same thing was that Thatcherism was defined by its hostility to the

unions, and its

reduction of the top rates of income tax, rather than its hostility to the welfare state.

I think these points are important if we want to address an apparent paradox.

As

this video illustrates (

here is

the equivalent for the US), growing inequality is not popular. Fairness

is up there with liberty as a universally agreed goal, and most people

do not regard the current distribution of income as fair. In addition,

evidence that inequality is associated with many other ills is becoming

stronger by the day. Yet the UK opposition today retains the previous government’s

reluctance to campaign on the subject.

This paradox appears all the more perplexing after the financial

crisis, for two reasons. First the financial crisis exploded the idea

that high pay was always justified in terms of the contribution those

being paid were making to society. High paid bankers are one of the most

unpopular groups in society right now, and it would be quite easy to

argue that these bankers have encouraged other business leaders to pay

themselves more than they deserve. Second, while Thatcherism did not

attempt to roll back the welfare state, austerity has meant that the

political right has

chosen to paint poverty as laziness. As a result, reducing poverty is

no longer an uncontroversial goal.[2]

What is the answer to this paradox? Why is tackling inequality not

seen as a vote winner on the mainstream left? I can think of two

possible answers, but I’m not confident about either. One, picking up

from the historical experience I discussed above, is that reducing

inequality is still connected in many minds with increasing the power of

trade unions, and this is a turn-off for voters. A second is that it is

not popular opinion that matters directly, but instead the opinion of

sections of the media and business community that are not forever bound

to the political right. Politicians on the left may believe that they

need some support from both sectors if they are to win elections.

Policies that reduce poverty, or reduce unemployment, do not directly

threaten these groups, while policies that might reduce the incomes of

the top 10% do.

This leads me to one last argument, which extends a

point made

by Paul Krugman. I agree with him that “we know how to fight

unemployment — not perfectly, but good old basic macroeconomics has

worked very well since 2008…. The causes of soaring inequality, on the

other hand, are more mysterious; so are the channels through which we

might reverse this trend. We know some things, but there is much more

room for new knowledge here than in business cycle macro.” My extension

would be as follows. The main reason why governments have failed to deal

with unemployment are accidental rather than intrinsic: the best

instrument available in a liquidity trap (additional government

spending) conflicts with the desire of those on the right to see a

smaller state. (Those who oppose all forms of stimulus are still a

minority.) In contrast, reversing inequality directly threatens the

interests of most of those who wield political influence, so it is much

less clear how you overcome this political hurdle to reverse the growth

in inequality.

[1] This association is of course encouraged by the political right,

which is quick to brand any attempt at redistribution as ‘class war’.

[2] The financial crisis did allow the Labour government to create a new top rate of income tax equal to 50%, but this was

justified on

the basis that the rich were more able to shoulder the burden of

reducing the budget deficit, rather than that they were earning too much

in the first place.

This post was first published on Mainly Macro

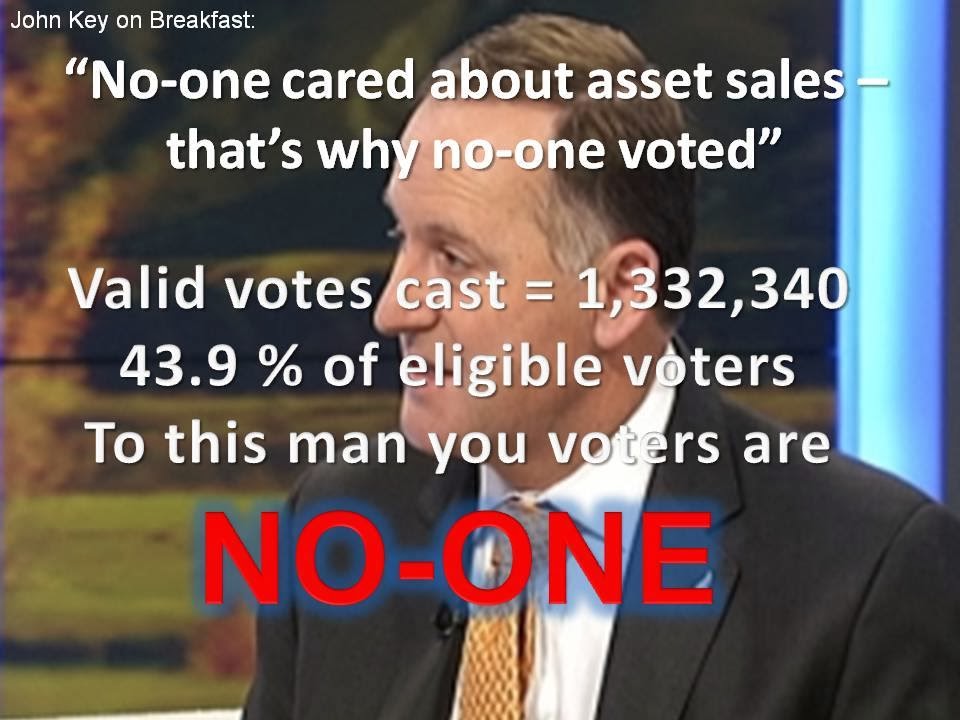

One only has to scan the headlines of the NZ newspapers to see how this message is reiterated until it has sunk into the subconscious thinking of voters. From opinionista pieces advocating further tax cuts, arguing that there are too many divides in the opposition to be credible governments compared to the over-whelming arrogance of the neo-liberal, asset selling Key led National-Act Government, that asset sales are of great economic benefit to NZ voters, to puff pieces promising greater futures based on the "aspirational" purchasing power of the privileged 1% we are being "stroked" into accepting the belief that since the advent of the Key-English New Zealand has never had it so good and that Key, a creation of the PR company, Crosby-Textor, can walk on water.

One only has to scan the headlines of the NZ newspapers to see how this message is reiterated until it has sunk into the subconscious thinking of voters. From opinionista pieces advocating further tax cuts, arguing that there are too many divides in the opposition to be credible governments compared to the over-whelming arrogance of the neo-liberal, asset selling Key led National-Act Government, that asset sales are of great economic benefit to NZ voters, to puff pieces promising greater futures based on the "aspirational" purchasing power of the privileged 1% we are being "stroked" into accepting the belief that since the advent of the Key-English New Zealand has never had it so good and that Key, a creation of the PR company, Crosby-Textor, can walk on water.